“Life was good because the land was the land of our ancestors. The village was along the riverside, where you could get drinking water, go fishing and plant mango, banana and papaya. The temperature there was good and we could feed ourselves.”

This is how Mr O – his name is protected for his safety – remembers the home he shared with his family in the Gambella region of Ethiopia. The fertile land had been farmed for generations, relatively safe from wars, revolutions and famines. Then, one day, near the end of 2011, everything changed. Ethiopian troops arrived at the village and ordered everyone to leave. The harvest was ripe, but there was no time to gather it. When Mr O showed defiance, he says, he was jailed, beaten and tortured. Women were raped and some of his neighbours murdered during the forced relocation.

Using strongarm tactics reminiscent of apartheid South Africa, tens of thousands of people in Ethiopia have been moved against their will to purpose-built communes that have inadequate food and lack health and education facilities, according to human rights watchdogs, to make way for commercial agriculture. With Orwellian clinicalness, the Ethiopian government calls this programme “villagisation”. The citizens describe it as victimisation.

And this mass purge was part bankrolled, it is claimed, by the UK. Ethiopia is one of the biggest recipients of UK development aid, receiving around £300m a year. Some of the money, Mr O argues, was used to systematically destroy his community and its way of life. Now this lone subsistence farmer is taking on the might of Whitehall in a legal action; a hearing took place in the high court in London last Thursday, but judgment on whether the case can go ahead has been reserved. Mr O and his legal team now await a decision on permission from the judge, who will declare whether there is an arguable case that can go forward to a full hearing.

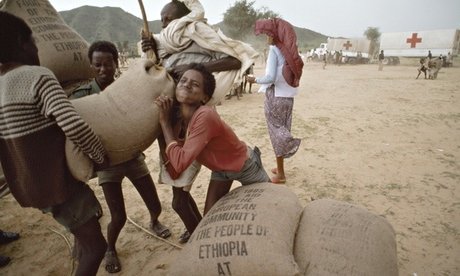

“The British government is supporting a dictatorship in Ethiopia,” says Mr O, speaking through an interpreter from a safe location that cannot be disclosed for legal reasons. “It should stop funding Ethiopia because people in the remote areas are suffering. I’m ready to fight a case against the British government.” The dispute comes ahead of the 30th anniversary of famine in Ethiopia capturing the world’s gaze, most famously in Michael Buerk’s reports for the BBC that sparked the phenomena of Band Aid and Live Aid. Now, in an era when difficult questions are being asked about the principle and practice of western aid, it is again Ethiopia – widely criticised as authoritarian and repressive – that highlights the law of unintended consequences.

Mr O is now 34. He completed a secondary-school education, cultivated a modest patch of land and studied part-time at agricultural college. He married and had six children. That old life in the Gambella region now seems like a distant mirage. “I was very happy and successful in my farming,” he recalls. “I enjoyed being able to take the surplus crops to market and buy other commodities. Life was good in the village. It was a very green and fertile land, a beautiful place.” So it had always been as the seasons rolled by. But in November 2011 came a man-made Pompeii, not with molten lava but soldiers with guns. A meeting was called by local officials and the people were told that they had been selected for villagisation, a development programme the government claims is designed to bring “socioeconomic and cultural transformation of the people”.

Mr O says: “In the meeting the government informed the community, ‘You will go to a new village.’ The community reacted and said, ‘How can you take us from our ancestral land? This is the land we are meant for. When a father or grandfather dies, this is where we bury them.'”

The community also objected to the move because they feared ethnic persecution in their proposed home and because the land would not be fertile enough to farm. “Villagisation is bad because people were taken to an area which will not help them. It’s a well-designed plan by the government to weaken indigenous people.”

So in 2012 he dared to return to his old village and tried to farm his land. It was a doomed enterprise. In around April, he claims, he was caught and punished for encouraging disobedience among the villagers. Soldiers dragged him to military barracks where he was gagged, kicked and beaten with rifle-butts, causing serious injuries. He was repeatedly interrogated as to why he had come back. “I went to the farm and was taken by soldiers to military barracks and locked in a room,” Mr O recalls. “I was alone and beaten and tortured using a gun. They put a rolled sock in my mouth. The soldiers were saying: ‘You are the one who mobilised the families not to go to the new village. You are also inciting the people to revolution.’ Other people were in different rooms being tortured, some even killed. Some women were raped. By now they have delivered children: even now if you go to Gambella, you will meet them.” He reflects: “I felt very sad. I had become like a refugee in my homeland. They did not consider us like a citizen of the country. They were beating us, torturing us, doing whatever they want.”

In fear for his life, Mr O fled the country. The separation from his wife and children is painful. He communicated indirectly with them last year through a messenger. “I am sad. The family has no one supporting them. I am also sad because I don’t have my family.”

But such is the terror that awaits that, asked if if he wants to return home, he replies bluntly: “There’s nothing good in the country so there is nothing that will take me back.”

Modern Ethiopia is a paradox. A generation after the famine, it is hailed by pundits as an “African lion” because of stellar economic growth and a burgeoning middle class. One study found it is creating millionaires at a faster rate than any other country on the continent. Construction is booming in the capital, Addis Ababa, home of the Chinese-built African Union headquarters. Yet the national parliament has only one opposition MP. Last month the government was criticised for violently crushing student demonstrations. Ethiopia is also regarded as one of the most repressive media environments in the world. Numerous journalists are in prison or have gone into exile, while independent media outlets are regularly closed down.

Gambella, which is the size of Belgium, has a population of more than 300,000, mainly indigenous Anuak and Nuer. Its fertile soil has attracted foreign and domestic investors who have leased large tracts of land at favourable prices. The three-year villagisation programme in Gambella is now complete. A 2012 investigation by Human Rights Watch, entitledWaiting Here for Death, highlighted the plight of thousands like Mr O robbed of their ancestral lands, wiping out their livelihoods. London law firm Leigh Day took up the case and secured legal aid to represent Mr O in litigation against Britain’s international development secretary, whom it accuses of part-funding the human rights abuses.

Mr O explains: “The Ethiopian government is immoral: it is collecting money on behalf of poor people from foreign donors, but then directing it to programmes that kill people. At the meeting, the officials said: ‘The British government is helping us.’ Of all the donors to Ethiopia, the British government has been sending the most funds to the villagisation programme. “I’m not happy with that because we are expecting them to give donations to support indigenous people and poor people in their lands, not to create difficult conditions for them. They should stop funding Ethiopia because most of the remote areas are suffering. The funds given to villagisation should be stopped.” Mr O did not attend last week’s court hearing at which Leigh Day argued that British aid is provided on condition that the recipient government is not “in significant violation of human rights”. It asserted that the UK has failed to put in place any sufficient process to assess Ethiopia’s compliance with the conditions and has refused to make its assessment public, in breach of its stated policy.

Rosa Curling, a solicitor in the human rights department at Leigh Day, says: “It’s about making sure the money is traced. When you’re handing over millions of pounds you have a legal responsibility to make sure the money is being used appropriately. The experience of the village is absolutely appalling. We’re saying to the Department for International Development (DfID), please look at this issue properly, please follow the procedure you said you would follow, please talk to the people who’ve been affected. Look at what happened to Mr O and his village. They haven’t done that.”

Mr O offered to meet British officials, she adds, but they decided his refugee camp was too dangerous. He offered to meet them in a major city, but still they refused. “They haven’t met anybody directly affected by villagisation.” Curling urges: “If you’ve got money, trace it and put conditions on it so it’s not being used like this. It completely defeats the point of aid if it’s being used in this way. We’re talking about millions of British pounds.”

The view is echoed by Human Rights Watch. Felix Horne, its Ethiopia and Eritrea researcher, says: “Given that aid is fungible, DfID does not have any mechanism to determine how their well-meaning support to local government officials is being used in Ethiopia. They have no idea how their money is being spent. And when they are provided [with] evidence of how that money is in fact being used, they conduct seriously flawed assessments to dismiss the allegations, and it’s business as usual.

“While they have conducted several ‘on the ground’ assessments in Gambella to ascertain the extent of the abuses, they have refused to visit the refugee camps where many of the victims are housed. The camps are safe, easy to access, and the victims of this abusive programme are eager to speak with DfID, and yet DfID and other donors have refused to speak with them, raising the suspicion that they aren’t interested in hearing about abuses that have been facilitated with their funding.”

DfID is set to contest the court action, denying that any of its aid was directly used to uproot Mr O or others affected by villagisation. A spokesman says: “We will not comment on ongoing legal action. The UK has never funded Ethiopia’s resettlement programmes. Our support to the Protection of Basic Services Programme is only used to provide essential services like healthcare, schooling and clean water.” Shimeles Kemal, the Ethiopian government’s state minister of communications, was unavailable for comment.