Women’s Bodies as Battlefields: Breast Amputation and Genital Mutilation by The Nobel Peace Laureate Abiy Ahmed Ali’s Soldiers. A tribute to Bealem Wasse

Contact information:

Girma Berhanu, Professor

Gothenburg University

Department of Education and Special Education

Abstract

The situation in Ethiopia’s Amhara region has deteriorated into a critical humanitarian and human-rights emergency. Emerging evidence from besieged localities indicates an escalation of atrocities that transcend previously documented patterns of violence. Verified testimonies and secondary reports detail widespread killings accompanied by systematic sexual and gender-based violence, including acts intended to cause profound physical and psychological harm. These violations appear to be strategically employed as instruments of terror and social destabilization. The proliferation of graphic content across digital platforms has generated significant secondary trauma among affected populations, while simultaneously underscoring the role of media in shaping collective perception and response. Notwithstanding the severity of these crimes, international awareness and condemnation remain disproportionately limited, revealing a persistent gap between global normative commitments and practical engagement. Concurrently, ongoing drone strikes against civilian populations exacerbate the humanitarian toll, contributing to cumulative suffering and displacement. Drawing on verified interviews with relatives of victims and triangulated findings from human-rights and academic sources, this study situates the documented abuses within the broader context of conflict-related sexual violence and violations of international humanitarian law. Building on prior research concerning gendered violence against men in the region, the findings contribute to a growing body of empirical evidence suggesting the commission of acts that may amount to crimes under international law.

Introduction

ፋኖ ፋኖ አለቺኝ፣ ፈንን ያርጋትና

ተኳሹ፣ ፈራሹ፣ ማለቷ ቀረና።

ቀሚሴም አለቀ፣ ተባኖ፣ ተባኖ

ኩታዬም አለ ቀ፣ ተባኖ ተባኖ

አሁን ያለብሰኛል፣ ስደተኛው ፋኖ።

ፋኖ ፋኖ አለቺኝ፣ ፋኖን እንደዋዛ

ማነው የተዋጋው፣ “ጥሊያን” እንዳይገዛ።

ኧረ ጥራኝ ጫካው፣ ኧረ ጥራኝ ድሩ

ላንተም ይሻለሀል፣ ብቻ ከማደሩ።

The situation in the Amhara region, Ethiopia has taken an increasingly disturbing turn. Reports emerging from the besieged areas describe atrocities that surpass the brutality already associated with the conflict. Beyond the widespread killings, evidence indicates extreme sexual and gender-based violence. Accounts include the severing of breasts, genital mutilation, and systematic sexual assault directed at young girls and women as well as men.

These newly alleged crimes in multiple districts have shocked local communities. Graphic images circulating across social media have provoked profound distress and psychological harm among those exposed to them. Despite the severity of these violations, there has been minimal global media attention and insufficient international condemnation. The silence of the international community remains deeply concerning.

The atrocities coincide with ongoing drone strikes against civilian populations, further intensifying human suffering. This report incorporates verified information obtained from relatives of victims, alongside firsthand testimonies corroborated through existing academic and human-rights literature. Notably, the same author has previously documented male rape, genital mutilation, and other forms of conflict-related sexual violence against men in the region.

These findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting the occurrence of large-scale, targeted violations that may constitute crimes under international law. Since the onset of the conflict in the Amhara region—widely regarded as having been precipitated by actions of the federal government—the behavior of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and senior political leaders, including the Prime Minister, has increasingly exhibited characteristics associated with repressive or coercive state violence. In contrast, Fano forces have at times portrayed themselves, and been perceived by some local actors, as more legitimate and disciplined entities within the region. Developments over the past two to three weeks have further highlighted this complex and paradoxical dynamic.

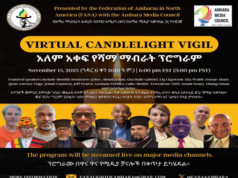

The preliminary findings reveal a disturbing and systematic pattern of violence targeting adolescents and young women, as described by multiple witnesses. Reported atrocities include forced breast amputation, violent rape often accompanied by beatings, stabbings, and burning, and the insertion of foreign objects resulting in severe genital injuries. Executions followed by the public display of bodies appear intended to terrorize and subjugate entire communities. A particularly illustrative case is that of Bealem Wasse, a wounded prisoner of war whose breast was severed and the skin flayed from her hand, revealing a tattoo reading “I am Amhara,” symbolizing the deliberate targeting of identity and the intent to inflict permanent collective trauma. Acts of genital and physical mutilation have reportedly occurred in public settings, designed to degrade victims and dismantle community morale through shock, shame, and grief. Three young girls from different parts of the Amhara region have been tragically killed, their bodies mutilated in the same horrific way. Candlelight vigils are being held around the world to mourn them and stand against this cruelty. See one of the photos from the vigil below. To exacerbate the situation, reports indicate that the families of the mutilated and murdered girls have been subjected to detention and intimidation. According to multiple local accounts, relatives of victims are currently imprisoned and have been warned by security forces not to disclose information regarding the mutilations to foreign observers or media outlets. In one verified instance, a father was allegedly coerced into publicly denying that he had witnessed his daughter’s injuries. Direct communication with one of the affected parents further corroborates the pattern of threats and suppression aimed at silencing witnesses and obstructing documentation of these violations.

Drone strikes have targeted residential areas and shelters, killing civilians—including survivors of sexual violence—and suggesting a coordinated, multi-layered campaign against noncombatants. Previous documentation of the rape and genital mutilation of male detainees and civilians indicates that sexual violence is being deployed strategically across gender lines rather than as isolated misconduct. The resulting psychological toll is profound, with communities reporting widespread trauma, depression, suicidality, and stigma, exacerbated by the online circulation of graphic images that deepen collective anguish. Legally, these patterns are consistent with war crimes and crimes against humanity—encompassing sexual violence, torture, and extrajudicial executions—as well as violations of international treaties, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

Biopolitics and Necropolitics: Power, Life, and Death in the Modern Political Order

Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and Achille Mbembe’s notion of necropolitics offer two influential frameworks for understanding the relationship between power, life, and death in modern political thought. Both theorists reveal how power extends beyond traditional notions of sovereignty, yet they differ in emphasis: Foucault focuses on the regulation and optimization of life, while Mbembe foregrounds the persistence of death as a mechanism of political control—an idea vividly illustrated in the case of the Amhara people.

In his late-1970s lectures and writings, particularly The History of Sexuality, Volume 1 (Foucault, 1978) and Society Must Be Defended (Foucault, 2003), Foucault argues that modern power signifies a transformation from the sovereign’s right “to take life or let live” to a new paradigm that seeks “to make live and let die.” This shift marks the emergence of biopower—a form of governance centered on the administration of life, health, reproduction, and population management. Power no longer operates primarily through repression or punishment, but through the regulation and optimization of biological existence. The modern state, through institutions such as medicine, education, and demography, works to foster life, discipline bodies, and manage populations. According to critical observers, the population of the Amhara people has been reduced to approximately seven million over the past 34 years—a figure that raises profound biopolitical questions about the management and neglect of life.

Achille Mbembe (2003), however, critiques the limits of Foucault’s framework, arguing that biopolitics insufficiently accounts for the historical and ongoing realities of colonialism, slavery, and contemporary warfare. In his essay Necropolitics, Mbembe contends that sovereignty continues to hinge on the power to decide who may live and who must die. He defines necropolitics as the use of social and political power to expose certain populations to death, producing what he calls “death-worlds”—spaces where people are reduced to a state of “living death,” stripped of political value and rendered disposable. Few frameworks capture more poignantly the tragedy that the Amhara people continue to endure.

For Mbembe, the colonial plantation, the occupied territory, and the concentration camp exemplify the spatialization of necropolitical power. Within these zones, the boundaries between life and death blur as certain groups—racialized, colonized, or otherwise dehumanized—are systematically subjected to violence and extermination. The racial logic of modernity, he argues, legitimizes this process by determining who counts as fully human and who does not. Necropolitics thus extends and deepens Foucault’s analysis by revealing that the management of life is inseparable from the production of death within the global order.

In conclusion, while Foucault’s biopolitics examines how modern power regulates and sustains life, Mbembe’s necropolitics exposes the ways in which sovereignty continues to operate through death. The two frameworks intersect to show that the politics of life and death are not opposites but deeply intertwined mechanisms of modern power. Mbembe’s critique ultimately reveals the colonial and racial underside of biopolitical modernity: the lives of some are preserved and optimized precisely through the abandonment, exposure, and destruction of others. To analyze Ethiopia through the lens of biopolitics and necropolitics is to recognize how the state governs who gets to live well, who is merely kept alive, and who may be left to die. This perspective reveals that modern Ethiopian politics—like that of many postcolonial states—is concerned not only with sovereignty and territory, but also with the uneven valuation of human life itself. In Ethiopia, biopolitics and necropolitics often coexist. The same state that builds hospitals and schools may also imprison, displace, or starve its population. Life-management and death-dealing are deeply intertwined; development and violence function as two sides of the same political rationality. Famine as a necropolitical event: Historically recurring famines in Ethiopia are not merely natural disasters but political phenomena. Decisions about resource allocation, access, and visibility determine who lives and who dies. This reflects Achille Mbembe’s notion of the politics of death, where state action—or inaction—effectively allows certain populations, in this case the Amhara, to perish.Ethnic federalism and zones of abandonment: Ethiopia’s system of ethnic federalism has sometimes produced differentiated forms of citizenship, granting some groups greater security and access to resources than others. Peripheral regions such as Afar, Somali, Gambella, and Benishangul-Gumuz have often been left in conditions of neglect—what Mbembe would describe as “death-worlds”—where life remains precarious and state presence is largely militarized.

Case Study: Bealem Wasse— A Young Life Shaped by Violence

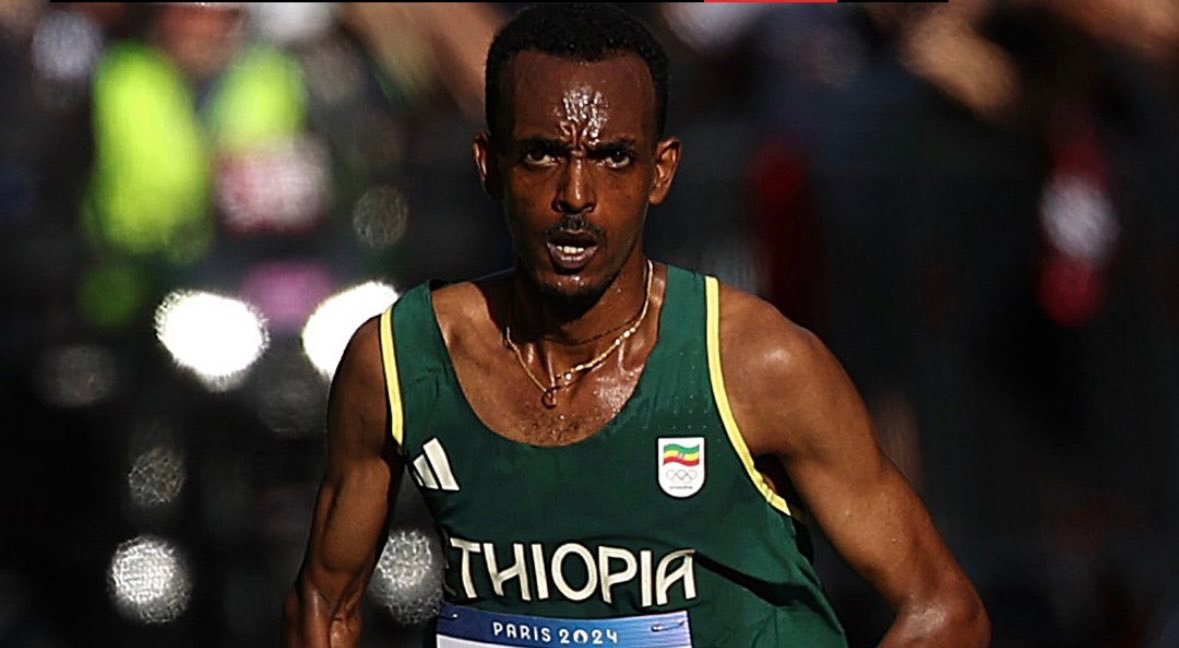

Bealem Kassye was a 19-year-old girl remembered by her friends and community as active, curious, and ambitious. She aspired to pursue studies in the arts and sciences and was preparing to begin ninth grade two years ago when she joined the Fano movement. Those who knew her describe her as courageous, respectful toward elders, and passionate about dancing and learning.

In an extensive interview, Fano leader Aynaddis Waleligne—a female member of the Fano movement, known locally as a Fanit, affiliated with the Tewodros Command in western Amhara and serving as head of women’s affairs—spoke about the brutal treatment of injured girls and women. According to Ayanaddis, “Bealem was born in Bure Woreda and was injured in and around Mankusa Zuria. Instead of receiving medical treatment in accordance with international standards, her breast was severed and the skin bearing her ‘Amhara’ tattoo was cut away. She was then left exposed, her body displayed publicly.”

Aynaddis attributed these acts of brutality to elements of the Oromo Special Forces, asserting that such operations occur as the government’s defense forces struggle to counter Fano defense strategies. Multiple witnesses reportedly confirmed viewing Bealem’s body; however, their identities are withheld for security reasons. Aynaddis, by contrast, consented to be identified by name, stating that she “has nothing to fear.”

According to people who witnessed her upbringing and spoke to investigators, Bealem’s decision to join the Fano resistance movement stemmed from her inability to tolerate the ongoing violence and persecution faced by the Amhara community. She had been deeply affected by reports of killings, rapes, and the destruction of civilian infrastructure in her region. Witnesses recalled her speaking often about the suffering of her people and the apparent absence of justice or protection.

Bealem was particularly disturbed by the systematic targeting of civilians: repeated drone strikes on gatherings, burning of villages, bombardment of places of worship, and mass executions of Amhara residents. Public buses were reportedly hijacked, and entire families were killed in her vicinity. She lamented that displacement had torn apart her community as many Amhara families were forced to flee to larger cities such as Bahir Dar in search of safety.

She reportedly questioned, “Where is God when my people suffer like this?”—a reflection of her despair amid the repeated atrocities committed against the Amhara population. Bealem spoke of how the fundamental rights to life, safety, and free movement had been denied to her community, while state authorities failed to offer protection or accountability.

Witnesses also described her frustration at what she perceived as government indifference to civilian suffering. As massacres, rapes, and mass displacements continued, official attention often shifted to symbolic public relations events, such as tree-planting campaigns, widely seen by many citizens as hollow gestures in the face of ongoing atrocities.

Bealem’s reflections in the year before her death reveals the emotional and moral toll that prolonged violence and impunity have inflicted on Ethiopia’s youth. Her decision to join the Fano movement—reportedly with the understanding and support of those closest to her—was not driven by ideology alone, but by a sense of desperation and moral duty in the face of what she perceived as the systematic destruction of her community.

Refugee International

Fano: Resistance, Intellectualism, and the Legacy of Bealem Wasse

Fano emerged as a response to systematic injustice. Bealem Wasse was not only a brave fighter but also an articulate thinker, capable of analyzing the dangers facing her country. Fano, as a movement, is not merely a physical resistance; it represents an intellectual and moral stance against ethnic fascism, narrow nationalism, apartheid-like policies, internal colonialism, and pseudo-legal forms of political corruption. Instead, it upholds civic responsibility, patriotism, and a vision for the common good of Ethiopia. Informants describe Bealem as embodying these principles fully.

The movement draws inspiration from the historical Fano resistance against the Italian occupation, with current members proudly linking themselves to that heritage. Cultural expressions, such as poems and songs, are being created to honor Bealem’s heroism and the broader sacrifices of Fano fighters.

Despite being an unpaid, under-resourced, and self-armed volunteer defense group, Fano has proven to be a significant force in defending the Amhara population and resisting the ongoing campaign of violence. The group has conducted successive, strategic offensives against hostile forces in the Amhara region, prioritizing the safety of civilians and the preservation of Ethiopia’s unity. Their reputation is grounded not in seeking glory, but in protecting their people from annihilation. Fano fighters are widely regarded as the embodiment of the Amhara spirit and defenders of Ethiopia throughout history.

Bealem’s legacy calls for commemoration and remembrance. Future generations should be assured that the sacrifices of young heroes like her are honored—through flowers that bloom year-round, commemorative events, and public celebrations recognizing the courage and selflessness of Fano fighters. These acts of remembrance would celebrate the lives of those who gave everything for the survival of their people.

Today, the world feels a little darker. A bright flame, Bealem’s spirit, has been extinguished by systematic violence, yet her legacy continues. She was neither wealthy nor famous, but she impacted countless lives, inspired emerging Fano fighters, and embodied the values of honor, courage, and selflessness. Bealem is a true unsung hero.

In her 19 years, Bealem experienced more suffering and injustice than most could imagine. Yet, a friend recalls, she never complained. Instead, she faced adversity with determination, embodying the principle of resilience: when life presents challenges, she made the best of them and turned them into action. Bealem’s life is a testament to courage, moral conviction, and the enduring fight for justice.

Patterns of Violence: Historical Continuities and Modern Manifestations

Historical records and oral traditions suggest that acts of body mutilation were once part of initiation and warfare practices in certain Oromo cultural contexts. In some regions, a young man was not considered mature enough for marriage until he had killed a member of another tribe, with severed body parts of the victim sometimes displayed as proof of the deed—acts that were valorized within the warrior ethos of the time. During the reign of Emperor Menelik II, such practices, along with slavery and other inhumane customs, were gradually outlawed. It is worth noting, however, that Menelik’s governance displayed quasi-federal characteristics, often allowing a degree of autonomy among the constituent states of Ethiopia. Nevertheless, his patience was tested on several occasions—most notably when Negus Tona of Wolayta was compelled to abdicate due to his refusal to abolish slavery.

The prohibition of body mutilation among the Oromo—who had by then become an integral part of the Ethiopian polity—symbolically transformed certain cultural expressions. The traditional wooden object known as Kelecha, which replaced the real body parts once used as proof of bravery, endures as a cultural artifact bearing the weight of centuries-old collective trauma. The full extent of the human, linguistic, and cultural losses incurred during the historical Oromo expansions remains insufficiently studied. In a society where open critique of historical narratives has often been discouraged, and where ethnicity has become highly politicized, such inquiries have rarely found space in mainstream public discourse.

While this article does not aim to examine these cultural dynamics in depth, it draws attention to patterns of violence that have re-emerged since the current Oromo-led government came to power. The rhetoric and tactics displayed by some actors within the state apparatus and armed forces—most notably the Oromo-dominated divisions of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF)—show unsettling continuities with earlier historical patterns of conquest and expansion. Reports of extreme brutality, including targeted attacks against civilians, echo the violent practices associated with the Oromo expansions of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Early Oromo nationalist ideologues openly articulated their ambition to dismantle the Ethiopian state and establish a “Greater Oromia.” Scholars such as Asafa Jalata constructed theoretical foundations for this vision, framing the Oromo as victims of a “colonial” Abyssinian domination that allegedly destroyed an idealized precolonial democratic order known as the Gadaa system. Within this narrative, Emperor Menelik II has been portrayed by some as having committed “genocide” against the Oromo—a claim historically implausible given that Ethiopia’s total population in the 1800s was estimated at fewer than eight million. Nevertheless, these narratives have proven influential in nurturing resentment toward the Amhara population, who are often cast as the historical oppressors in this discourse.

Over time, victimhood rhetoric evolved into an exclusionary and, at times, openly genocidal ideology, portraying the Amhara as the source of all historical and contemporary injustices. Eyewitness accounts and survivor testimonies from recent years reveal patterns of extreme, often sadistic violence reminiscent of earlier centuries. The critical distinction today lies in the role of the state: elements of the Oromia Special Forces have not only tolerated such violence but, according to multiple reports, have participated directly in massacres targeting ethnic Amharas across various parts of the Oromia region.

These patterns suggest that the logic of domination and exclusion once rooted in historical conquest narratives has been reactivated and repurposed within the modern Ethiopian political landscape, now reinforced by state institutions and militarized structures.

Civilians as Targets: Hatred as a Driving Force

The government’s recent military operations have intensified civilian suffering and further exposed systemic problems in how political power and law enforcement are exercised in Ethiopia. Among the most troubling dynamics is the apparent targeting of Amhara civilians, reflecting a pattern of ethnically motivated violence that has evolved over decades.

For nearly half a century, anti-Amhara sentiment has featured prominently in Ethiopian political discourse. This hostility, cultivated by successive regimes and amplified by ethno-nationalist movements, has given rise to a range of political and armed groups. While differing in ideology, many share a common thread of Amhara-phobia—a narrative framing the Amhara as historical oppressors or obstacles to political transformation. Under the former Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) government, this rhetoric became institutionalized and shaped state policy. In recent years, it appears to have found renewed resonance under the Oromo-led administration.

Official statements by senior government figures, including the Prime Minister, as well as actions such as restrictions on the movement of ethnic Amharas, mass arrests, and discriminatory practices in law enforcement, have reinforced perceptions that the Amhara population is being systematically marginalized. The Amhara—owing to their demographic size, cultural influence, and historical role in state formation—are widely perceived as the main obstacle to the political dominance sought by the ruling Prosperity Party (PP) and its Oromo leadership.

Reports from affected regions suggest that state security forces, including divisions of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and the Oromia Special Forces, have engaged in or failed to prevent widespread violations against Amhara civilians. These include extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, destruction of property, and displacement. In several documented cases, civilian sites—including schools, churches, and health facilities—have been shelled or used for military purposes. Witness accounts have described acts of mutilation and other degrading treatment, which appear intended to terrorize and humiliate the Amhara community.

Anti-Amhara sentiment has also been instrumentalized to incite mob violence. Following the killing of Oromo singer Hachalu Hundessa, coordinated and spontaneous attacks occurred against Amhara, Gurage, and Gamo civilians across several regions. The authorities’ failure to prevent or respond effectively to these atrocities—and in some cases, their alleged complicity—has deepened a sense of insecurity among non-Oromo populations residing in the Oromia region. It is estimated that approximately 15 million non-Oromos, the majority of them Amharas, live in Oromia, where many face harassment, displacement, or detention.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC)—a historic institution central to Amhara cultural and spiritual identity—has also become a target of politicized division. The establishment of a breakaway synod led primarily by Oromo clergy, justified by claims of ethnic underrepresentation, has been perceived by many as an attempt to fragment the Church along ethnic lines. Drone strikes and artillery shelling against monasteries and churches—resulting in significant civilian casualties, including monks, priests, and worshippers—further suggest a pattern of deliberate or reckless attacks on religious and cultural heritage sites.

These developments indicate that ethnic hatred and exclusionary politics are being used not only as tools of mobilization but also as mechanisms of state control. The deliberate dehumanization of a specific group, coupled with the systematic use of state and non-state violence, underscores the urgent need for independent investigation into possible crimes against humanity, ethnic persecution, and attacks on cultural and religious heritage under international law.

Caveats, Verification Issues, and Gaps in the Evidence

Multiple credible reports have documented incidents of mutilation and reproductive harm against women and girls. However, comprehensive prevalence data—particularly regarding acts such as breast severing—remain limited. Most available information originates from survivor and witness testimonies, medical records, advocacy reports, and investigative journalism, rather than from peer-reviewed epidemiological or forensic studies.

The absence of large-scale quantitative evidence does not indicate that these acts did not occur. Instead, it reflects the challenges of systematic documentation in active or recently closed conflict zones, where conditions often include:

Due to these constraints, independent verification has been significantly limited. Investigators, including the author, have therefore relied on indirect evidence such as remote interviews, corroborated testimonies, and photographic or medical documentation provided by witnesses, health workers, and local human rights monitors.

Importantly, the targeting of women’s bodies in this context is not incidental or random. It often represents a deliberate strategy of terror and humiliation, aimed at the destruction of community cohesion and the erasure of ethnic identity. Acts such as the severing or mutilation of breasts or genitals serve both symbolic and functional purposes—symbolically attacking womanhood, motherhood, and reproduction, and structurally inflicting lasting physical, psychological, and social harm. These acts impose stigma, disrupt families, and fracture communities, contributing to long-term patterns of displacement and collective trauma.

Bibliography

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality, Volume 1: An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (2003). “Society must be defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976 (D. Macey, Trans.). Picador.

Mbembe, A. (2003). Necropolitics (L. Meintjes, Trans.). Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11

Lewis, Dustin (2009) “Unrecognized victims: sexual violence against men in conflict settings under international law.” Wisconsin International Law Journal, 27(1): 1-50.

Sorsoli, Lynn et al. (2008) “ ‘I keep that hush-hush:’ male survivors of sexual abuse and the challenges of disclosure.” Journal of Counselling Psychology, 55(30): 333-345.

Walker, Jayne, John Archer and Michelle Davies (2005) “Effects of rape on men: A descriptive analysis.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34 (1): 69-80.

Peel, M. (Ed.). (2004). Rape as a Method of Torture. Medical Society for the Care of Victims of Torture.

Depicted below is a grieving mother displaying her daughter’s outfit, a tangible reminder of the life taken from her. Her grief reverberates through a community bound by pain and absence; in her eyes rests the reflection of an entire people forced to bear the unbearable.