Bearing the Weight of Conscience: Alienation and Moral Dissonance in Humanitarian–Political Activism in Ethiopia and its Diaspora

“Human beings are perhaps never more frightening than when they are convinced beyond doubt that they are right.”—Laurens van der Post

Girma Berhanu, Professor

Gothenburg University

Department of Education and Special Education

Introduction

Over time, I have become increasingly weary of my fellow citizens—to the extent that I often feel estranged from my own cultural milieu and uncertain about the collective psychology, moral disposition, and behavioral tendencies of the society I inhabit. This sense of detachment contrasts sharply with the understanding I once held during the first four decades of my life, when I believed I shared a coherent cultural identity and a broadly shared moral vision with my community.

This transformation in perception became particularly pronounced through my humanitarian activism, especially in efforts to advocate for the downtrodden, marginalized, and systematically discriminated groups within my region. In striving to be a voice for the oppressed—those subjected to structural violence and, in some instances, mass atrocities—I encountered profound challenges not only from authoritarian institutions but also from the very communities whose emancipation I sought to advance. This reflective essay is grounded in autoethnographic research, characterized by an ongoing process of critical reflection and inquiry, conducted across multiple sites and utilizing multiple data sources, and informed by postmodern and critical theoretical perspectives. As a teacher of research methodology and philosophy of science, I have been particularly attentive to ethical considerations and have strived to uphold methodological rigor, transparency, and integrity throughout the research process.

I have reviewed the literature on the psychological and ethical challenges of humanitarian and activist work, including studies on moral dissonance, social alienation, and the tension between ethical commitment and personal well-being, such as Alienation and Moral Dissonance: The Psychological Cost of Humanitarian Activism, Struggling for the Oppressed: Ethical Commitment and Social Estrangement in Activism, Moral Fatigue and Social Alienation: Reflections on Humanitarian Engagement under Authoritarianism, Between Duty and Disillusionment: The Paradox of Advocating for Marginalized Communities, and The Burden of Moral Agency: Alienation, Dissonance, and Activism in Repressive Contexts. A comprehensive analysis of each theme would require extensive discussion; therefore, this essay focuses specifically on one strand: alienation and moral dissonance in humanitarian activism. A recent experience, which I shared on Facebook while writing this reflection, illustrates this point and provides a starting point for the discussion that follows.

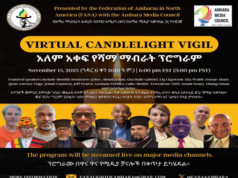

I wrote this yesterday, trying to make sense of a moment that unsettled me in ways I could not immediately name—a moment shaped by fellow countrymen and by the old homeland that lives within us long after we leave it behind. It unfolded during the funeral of our dear Mulugeta Woldegiorgis, Major Dawit’s older brother. In the stillness of shared grief, a man moved toward me with hurried steps, his words dissolving almost as soon as they formed. His presence felt charged—unquiet—as though he carried a storm looking for a place to break. He mumbled we had met “last year,” though it has been nearly eight. [ He seems upset with me, and I’m not sure why]. I had long sensed a restlessness in him, an agitation that seldom found language, yet I did not expect such an abrupt swell of emotion. Those brief ten seconds felt strangely disproportionate, as if they rose from a deeper wound—one invisible, but undeniably alive.Encounters like this draw me inward. There are moments when I feel the weight in another’s gaze before anything is spoken—a tension shaped not by the present alone, but by the histories, disappointments, and unresolved narratives each person carries quietly within them. Envy, misunderstanding, unprocessed pain, or something more existential—I can never fully know. I only know that I sense it. And when the atmosphere grows too dense, I withdraw. Not out of fear, but out of preservation—an acknowledgment that the inner life, too, requires boundaries if it is to remain intact. Yet what haunts me more deeply is the collective silence surrounding certain forms of suffering—the absence of even a single candlelight vigil for the Orthodox faithful killed in Arsi. No shared mourning. No communal gesture to affirm their humanity. In that void, silence became its own testimony—louder than lament, and far more revealing. It forced me to question my place within a church whose leaders seem unable—or unwilling—to shoulder the grief of their own people. Leadership without empathy becomes a hollow architecture; it shelters no one. And so, stepping back has become its own form of truth-telling: a way of honoring the limits of my spirit, of recognizing what I can carry and what I must lay down. Withdrawal, in this sense, is not abandonment but moral clarity. Even so, I choose the more difficult path—the path of bearing witness, of speaking for those who have been denied a voice. Advocacy, especially for the vulnerable, is always costly. But there is a price to silence as well, and in my view, that cost is far greater.https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1JsS7xFkec/

From a psychological perspective, such experiences can be interpreted through the lens of moral dissonance—the internal tension that emerges when deeply held ethical commitments conflict with the apathy, indifference, or hostility of others (Festinger, 1957; Tavris & Aronson, 2020). This cognitive-emotional conflict often leads to confusion, disillusionment, and moral fatigue among activists and humanitarians who dedicate themselves to causes of justice and human dignity (Lynch & McConatha, 2006).

Sociologically, this sense of estrangement resonates with the concept of alienation as articulated by Karl Marx (1844/1978) and later expanded by Erich Fromm (1955). Alienation describes the disconnection individuals feel from their social environment, community, and even from their own sense of purpose when societal structures undermine genuine human relations. Within activist contexts, alienation can manifest as the painful realization that one’s moral and political struggles are not always reciprocated by those who stand to benefit from them.

This paradox reveals a deeper crisis of collective identity. Social movements, by definition, depend upon solidarity and shared moral conviction; yet, under conditions of fear, propaganda, and authoritarian repression, societies often display fragmentation and internalized conformity (Scott, 1990; Arendt, 1973). The resulting dissonance between ethical commitment and social reality is not simply a personal confusion, but a reflection of broader sociopolitical distortions that erode mutual trust and collective consciousness.

In this light, the disillusionment I experience should not be regarded as an anomaly but rather as an existential byproduct of moral engagement under oppressive circumstances. It exemplifies what scholars have termed moral injury—the psychological cost of witnessing or enduring profound moral betrayal in social or political contexts (Litz et al., 2009). Thus, the confusion and emotional exhaustion that accompany humanitarian activism in repressive settings are not signs of weakness or inconsistency, but rather the inevitable outcome of sustaining ethical conviction in a world resistant to moral transformation.

Reflections on my journey in social activism and advocacy

During my sojourn in Sweden, I was primarily engaged as a student and junior researcher, without the security of a permanent residence permit. Even at that time, it was evident to me that the EPRDF/TPLF regime governed through an oppressive political architecture designed to weaken national cohesion and systematically marginalize the Amhara population. Numerous forms of state-linked atrocities emerged in conjunction with the rise and consolidation of this political order. I found it difficult to comprehend how societal relations had deteriorated to the extent that groups within the country appeared poised to undermine or even destroy one another.

Throughout most of the EPRDF period, my engagement in advocacy was limited. My contributions were modest and often undertaken anonymously. It was only with the expansion of the internet and social media that I began to participate more actively in socio-political discourse, primarily through academically oriented forms of activism.

During a research-related visit to the Netherlands, I observed that a disproportionate share of international scholarships was awarded to Tigrayan students or to government-aligned individuals from other ethnic groups, with Amhara applicants markedly underrepresented. This observation prompted a more systematic inquiry across ten universities abroad, through which I identified institutional patterns resembling an ethnic-based apartheid mechanism embedded within Ethiopia’s political order. The group favored by the ruling coalition was consistently overrepresented in competitive scholarship programs. Concurrently, I became aware of stark regional disparities in the allocation of educational resources. The Amhara region, in particular, appeared significantly disadvantaged. These findings revealed to me the depth and breadth of the systemic and structural inequalities—indeed, the apartheid-like conditions—prevailing in Ethiopia during this period.

Although I aimed to present my findings objectively and truthfully, members of the ruling elite responded with considerable hostility. The reaction made clear that my research had encroached upon politically sensitive terrain and threatened interests sustained through longstanding systems of exploitation.

My second major publication addressed the largely overlooked phenomenon of male sexual violence in Ethiopian prisons, with a particular focus on Amhara activists. While discourse on sexual violence in Ethiopia predominantly emphasizes female victims, male rape remains underreported and socially stigmatized, reflecting deep-seated cultural taboos that inhibit discussion. Initial responses from colleagues, acquaintances, and even close relatives discouraged me from pursuing this research, citing the sensitivity of the subject.

The impetus for this study originated from a survivor who contacted me from South Korea to disclose the systematic perpetration of sexual abuse by elements of the TPLF security apparatus. This disclosure provided both the empirical foundation and ethical imperative for the research. The publication elicited both recognition for its courage and condemnation from political authorities, highlighting the contentious and high-risk nature of research in politically sensitive contexts. This work marked my entry into the complex intersection of political advocacy, human-rights scholarship, and activism.

Subsequently, my research has expanded to encompass broader questions of structural injustice during the Abiyadministration, with particular attention to what I identify as genocidal acts targeting the Amhara population by state and non-state actors, including armed groups operating in the Oromia region. My scholarship has also examined the so-called Tigrayan conflict, military operations and sieges in the Amhara region, the use of drone strikes, the imprisonment of intellectuals, and reports of widespread human-rights abuses, including sexual violence and mutilation. Beyond immediate physical violence, my research explores systemic threats to Amhara language, Ge’ez, and cultural and historical heritage, situating these phenomena within broader patterns of ethnically targeted marginalization and state-sanctioned repression. Two of my monographs provide comprehensive analyses of these issues, contributing to a growing body of literature on ethnically structured violence, state repression, and the intersection of cultural and political rights in contemporary Ethiopia.

Over the past seven years, I have produced an estimated seventy or more articles on this subject, participated in numerous panel discussions, delivered keynote lectures, contributed financially to displaced populations, and travelled extensively at my own expense to raise awareness about the precarious situation facing marginalized Amhara communities. I recount these activities not as a form of self-promotion, nor as an attempt to portray myself as a model human rights advocate, but to contextualize the personal and professional implications of this sustained engagement. These efforts have entailed significant costs, including adverse effects on my health, strained relationships with various Ethiopian colleagues, financial burdens, and disruptions to my personal life. Consequently, I find myself occupying a different social and existential space, marked by distance from aspects of my earlier identity and accompanied by experiences of threats, hostile messages, disparaging commentary, and even attempts to involve my employer. My reactions to these developments have ranged from disbelief and sadness to frustration and, at times, resignation. Notably, some of the most severe criticisms and injurious remarks originate from individuals who identify themselves as Amharas. While I cannot ascertain the authenticity or depth of their identification, their rhetorical patterns are familiar across multiple platforms. I interpret such behavior as indicative of malice, envy, and limited constructive capacity, coupled with a propensity to undermine members of their own group. In this regard, I find resonance in a statement attributed to an African labor union activist: “When I fight colonialists, I do it with one hand because the other is occupied fighting my own people.”

Approximately one year ago, a term used in one of my publications was misinterpreted by several readers. It is no longer clear to me whether the wording originated from my initial draft or from later editorial adjustments. The article itself sought to address conceptual issues concerning the need for an Amhara struggle grounded within a broader and more inclusive Ethiopian framework. Nevertheless, the term in question was taken out of context and misrepresented as an indication that I favored one armed group over another—an interpretation that substantially departed from the text’s actual intent and likely stemmed from linguistic misunderstandings.

The resulting controversy became one of the most protracted and challenging episodes of my public engagement, extending over several months. Notably, only a limited number of individuals attempted to clarify the misinterpretation or defend the analytical focus of the article. Despite the sustained criticism, I remained professionally and intellectually resilient. During and after this period, I completed another monograph, published several further articles, and continued to participate actively in public discourse and advocacy. These efforts reflected my commitment to scholarly integrity and to maintaining an active presence in debates of significant societal consequence. This experience underscored for me the dangers posed by miscommunication and misrepresentation, aptly captured in the observation that “false knowledge is dangerous.”

From the outset, my engagement was frequently misconstrued

Already a few months after Mr. Abiy Ahmed assumed power, I observed a country descending into turmoil, marked by violent conflict and pervasive corruption. Based on developments on the ground and the political discourse at the time, I attempted to provide critical commentary. I noticed that many people were being misled by his rhetoric, which prompted me to write an article titled The Many Faces of AbiyAhmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia and Nobel Peace Laureate – Op-Ed. At that time, questioning Abiy Ahmed seemed almost unthinkable. In a nation exhausted by authoritarian rule, here was a prime minister who appeared to be pushing democratic reforms on a daily basis. As Africa’s youngest leader, he stood in stark contrast to the continent’s aging political elites, such as Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, Paul Biya of Cameroon, or Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea.

Ethiopians seemed to revere him, and global media echoed that admiration. One term encapsulated the phenomenon: “Abiymania.” He appeared to be a celebrity African leader making all the right gestures. Thousands of political prisoners were released, prominent exiles were welcomed back, and local media and journalists were ostensibly free to operate without harassment. Corruption, he promised, would be eradicated, and those who had benefited from it would be held accountable. The pinnacle of his early achievements was a sudden peace agreement with Eritrea, a nation long in a state of semi-conflict with Ethiopia, which ultimately earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019.

Who could reasonably question such a leader? Yet, some Ethiopians did, myself included. My first serious misgivings arose with the publication of his book Medemer, loosely translated as “Striving Together,” which was heavily publicized by the government and its allied media outlets. While promoted as a solution to Ethiopia’s political divisions, the book is not a rigorous work on governance or society, but rather a pseudo-philosophical treatise reminiscent of motivational self-help texts, such as Who Moved My Cheese?or The 7 Morning Routines of Successful People. To many readers, it bore an air of megalomaniac whimsy akin to Gaddafi’s Green Book: offering a little of everything, yet ultimately yielding little substance.

In my assessment, the Prime Minister appeared to exhibit multiple identities, each with distinct moods, behaviors, and public personas. “Abiy the Actor” is more affable than “Abiythe Preacher,” yet neither matches the ruthlessness of “Abiythe Prince.” One moment, Ethiopians are lectured on the virtues of responsible democratic governance—the Preacher at his most persuasive—only to be reminded that Abiy was purportedly “chosen” to lead at a young age, following a prophecy by his mother that he would become the seventh King of Ethiopia—the Actor. Today, political prisoners once again fill the nation’s jails, and ordinary students expressing dissenting views have been killed by government forces—the Prince in full display.

My critical assessments and writings concerning this political figure generated significant controversy, particularly among segments of the highly educated population. Many contended that he should be afforded an opportunity to demonstrate his intentions, reflecting the broader ambiguity and uncertainty that characterized the early phase of his leadership. The primary objective of my analysis was to caution readers against being influenced solely by rhetorical flourish or charismatic presentation, and to encourage a more rigorous and critical evaluation of emerging political developments. Several years later, some individuals expressed regret for having dismissed these concerns, and others even noted—half in jest—the apparent prescience of my observations. Importantly, my conclusions were not grounded in conjecture or prediction, but in systematic observation, critical reasoning, and careful attention to empirical detail.

Responses from certain members of the Pentecostal community—as well as from other evangelical or Prosperity Gospel congregations—were particularly pronounced, shaped by the belief that any critique of the leader constituted an affront to a figure perceived as divinely sanctioned. Indeed, this form of quasi-worship of the new leader appeared to be widespread, extending beyond Pentecostal circles to traditionally well-established churches and even to segments of the general public. Within these contexts, I observed an immediate and marked shift in attitudes toward me, including various expressions of disapproval articulated not only by Pentecostal adherents but also by individuals from other social and religious groups. Despite the challenges these reactions posed, I sought to uphold the principles of intellectual integrity, the ethical obligations inherent in scholarly inquiry, and the normative commitments that guide my engagement with both my community and my faith.

Experiencing Sociopolitical Advocacy and the Dynamics of Social Networks in Ethiopia/Diaspora

Engagement in sociopolitical advocacy and human rights activism often entails significant personal and relational costs. In the context of Ethiopia, my efforts to draw attention to the plight of marginalized populations have precipitated substantial disruption within my social networks. Relationships that were previously characterized by stability, mutual support, and emotional intimacy—including friendships, familial bonds, and networks of comradeship—have undergone profound strain. Instances of warmth and human-centered engagement have, in several cases, deteriorated into patterns of bitterness, interpersonal tension, and, occasionally, complete relational dissolution. Consequently, I have adopted strategies of social circumscription, limiting interactions to psychologically safe environments and minimizing participation in communal events and religious gatherings.

The rationale for my sustained engagement in activism, including media communication and written dissemination, has been to foreground the largely underrepresented humanitarian crisis affecting Ethiopian populations. However, the pursuit of principled advocacy has incurred measurable social costs, including the loss of numerous interpersonal relationships. Paradoxically, this work has also facilitated the development of transnational networks of support, with online acquaintances and sympathizers demonstrating understanding and solidarity across considerable geographic distance.

One salient example underscores the social complexities inherent in advocacy. Approximately five years ago, three acquaintances criticized my public discourse for emphasizing the suffering of the Amhara population, rather than framing all victims generically as “Ethiopians.” This critique neglected the structural and systemic dimensions of targeted violence. The Amhara community has been subject to deliberate, organized acts of marginalization and violence within Oromia and Benishangul regions—actions in which both governmental and regional authorities have been implicated. Accurately representing these events necessitates acknowledgment of the affected population; obfuscation of ethnic identity risks diminishing the specificity and political significance of the abuses. Such divergence in perception highlights the challenges of maintaining social ties with individuals whose understanding is influenced by politicized propaganda and limited access to critical information.

Further, my advocacy has been occasionally misconstrued as ethnonationalist or as a rejection of the broader Ethiopian national identity. These interpretations are analytically unfounded and fail to recognize the distinction between targeted human rights advocacy and ethnonationalist ideology. Notably, international media coverage has begun to document these issues, although representation remains limited within global policy discourse and humanitarian forums.

This account illustrates the intersection between individual activism, social relational dynamics, and structural political violence. It emphasizes the social, emotional, and ethical costs associated with advocacy in contexts of systemic human rights violations, while highlighting the potential for transnational solidarity and the dissemination of critical knowledge beyond localized sociopolitical constraints.

Empirically, I have lost contact with approximately ten former close friends in my place of residence, primarily due to my public advocacy for the Amhara cause. Additionally, tens of close relatives have limited their interactions with me, likely because of my critical stance toward the government. I also maintain fewer contacts with some long-standing friends who are either of Oromo descent or of mixed Oromo–Amhara heritage.

Paradoxically, media exposure has elevated my public profile, with many assuming that I possess comprehensive knowledge of Ethiopia’s complex political landscape. I am frequently invited to give speeches and participate in public discussions, even as I am increasingly distanced from former personal networks and supportive communities. Navigating this environment has been challenging, given the emotionally charged and often unpredictable behavior of individuals within these networks. This complexity motivated me to write two opinion articles: Political Activism and Emotional Labilities: The Case of Amhara Struggle for Survival in Ethiopia and Its Diaspora and Understanding Collective Trauma in Ethiopian Politics: A Case Study of the Amhara People.

In the first article, I employed a reflective and observational approach to political activism, focusing specifically on the social, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions of actors engaged in the Amhara struggle for democracy, freedom, and equality. I critically examine the frustration caused by certain individuals whose unpredictable behavior, lack of commitment, and irrational thinking undermine collective efforts. Although these individuals represent a minority, they have exerted disproportionate influence over online discussions and organizations advocating for democracy, particularly regarding the Amhara cause.

I argue that emotional labilities play a central role in shaping political activism, particularly within diaspora communities. In the Amhara diaspora, the historical grievances, systemic marginalization, and experiences of displacement generate highly charged emotional responses. These emotions often manifest in online spaces, facilitating both solidarity and division. While intense emotional engagement can motivate political action, it can also compromise strategic decision-making, foster fragmentation, and provoke internal conflicts. I have personally experienced significant emotional and social costs as a result of these dynamics, including strained relationships and burnout.

The second article examines how collective trauma constitutes a fundamental barrier to achieving peace, cohesion, and a unified national struggle in Ethiopia. Unaddressed historical and social trauma continues to shape personal identities and political behaviors, frequently to the detriment of collective efforts. Recognizing and addressing this trauma is therefore essential for fostering meaningful political change, sustaining unity among advocacy groups, and advancing the rights and survival of the Amhara people.

Together, these reflections underscore the complex interplay between personal networks, emotional dynamics, and political activism. They highlight the need for both analytical reflection and strategic planning to navigate the challenges of advocacy in contexts marked by historical injustice, systemic marginalization, and collective trauma.

Reflections on Diaspora, Identity, and Cultural Alienation

Over time, I have experienced a profound sense of estrangement from the country of my birth—a place and culture I once believed I understood intimately. What I once perceived as familiarity has, upon reflection, revealed itself as partial and at times illusory. This distancing has created a profound sense of alienation, yet it has not diminished my commitment to marginalized populations, the displaced, or innocent victims of political and social violence.

In a recent personal reflection shared on social media, I articulated the depth of this experience:

“I travelled thousands of kilometres to a land shaped by a history not my own, a culture woven from threads unfamiliar to me. Yet here, in Sweden, I found souls whose warmth met mine as if we had known each other across lifetimes—people with whom I share quiet laughter, thoughtful conversations, and a kindness that feels like home. Sometimes I wonder whether such bonds ever existed between me and those who share my blood or homeland. For here, among strangers who became companions, I discovered a depth of connection I once believed belonged only to memory or imagination. I no longer picture myself living elsewhere, nor returning to the place I once called home. I’ve come to understand that home is not a map or a birthplace, but the space where your spirit settles—where you speak freely, move lightly, and feel seen without explanation. When you find that place, you need not search backward for another.”

This reflection highlights the complexity of diasporic identity, illustrating that belonging is not necessarily determined by geography or ancestry but by the quality of interpersonal connections, emotional resonance, and a sense of freedom and recognition within a social environment. These insights resonate with theoretical perspectives on diaspora, social belonging, and cultural negotiation (Hall, 1990; Clifford, 1994), which emphasize the fluidity of identity and the transformative potential of cross-cultural encounters.

At the same time, this sense of estrangement carried a very personal ethical and emotional weight. I noticed myself holding back certain thoughts about my homeland—thoughts that felt too raw or unflattering to name. They were mixed with envy, even malicious envy at times, and with an inflated sense of self that I recognized, uncomfortably, as what might be called Mekofes. Confronting these feelings forced me to acknowledge how vulnerable and exposed the work of diaspora reflection can be. It reminded me that my own inner struggles must be held up to the light just as carefully as the cultural and historical realities I seek to understand.

From an early age, I internalized an idealized understanding of my homeland: a cradle of humanity, the site of one of the world’s oldest religious traditions, a civilization distinguished by literacy, foresight, humility, and moral rigor. The fading of these early convictions over time highlights the dynamic interplay between memory, idealization, and lived experience, raising important questions about cultural continuity, identity formation, and the role of historical consciousness in shaping personal and collective ethics.

Ultimately, my experiences suggest that diasporic identity is constituted not solely by origin, but through the navigation of social, emotional, and ethical landscapes that mediate belonging, commitment, and personal integrity. The negotiation of alienation and connection, loss and attachment, forms the basis for both personal reflection and scholarly inquiry into the lived realities of displacement, activism, and cultural memory.