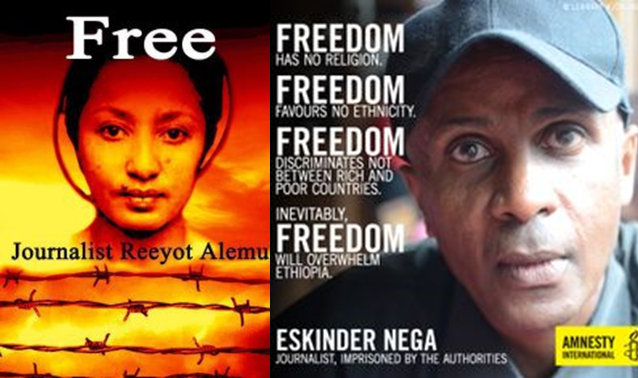

In July 2012, Eskinder Nega was sentenced to 18 years in prison. In June 2011, Reeyot Alemu was arrested and convicted to 14 years of imprisonment, reduced to five on appeal.

Their crimes? Practicing journalism in Ethiopia.

Nega and Alemu are award-winning journalists who shared the prestigious Human Rights Watch Hellman-Hammett Award in 2012. For Nega, whose first child was born while he and his wife were in custody for treason , the arrest came days after publishing a column that criticized the Ethiopian government’s detainment of journalists as suspected terrorists. For Alemu, a former high school English teacher, the arrest came days after she critiqued the ruling political party in an independent newspaper later shut down by the government.

The basis for the charges against these journalists isEthiopia’s 2009 Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, which contains overly vague provisions that have been used by the government to silence its critics. Since the Proclamation was adopted, more than 30 journalists have been convicted on terrorism-related charges.

Earlier this summer, I had the privilege of working on behalf of Nega and Alemu as a fellow with the Media Legal Defence Initiative (MLDI). The small London-based non-profit works directly with journalists and bloggers who have been prosecuted for exercising their protected right to freedom of expression. With the help of partner organizations, MLDI’s staff are currently working on 107 cases in 41 countries; the organization’s success rate in receiving favorable decisions hovers around 70 percent.

Because I studied journalism before coming to law school, I know the range of challenges American journalists face, from accessing information to protecting sources to the threat of civil liability. Still, it was always clear to me that the First Amendment by and large provides a greater amount of protection to journalists than any other national legal system. As my work at MLDI made clear this summer, freedom of expression is severely restricted in other countries—by censorship, regulations, state-operated monopolies, criminal liability, and physical threat, among others.

For example, on my very first day, I worked on a petition to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concerning the case of Le Quoc Quan, a Vietnamese human rights lawyer and blogger who was wrongfully prosecuted on trumped up charges of tax evasion. Throughout my internship, I also researched case law from regional courts on freedom of expression, helped with an amicus curiae submission before the High Court of South Africa in a case about criminal defamation, and worked on a case in defense of a blogger in Singapore who is being sued by Lee Hsien Loong, the country’s prime minister.

When Nani Jansen, MLDI’s legal director, filed a submission to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights on behalf of Nega and Alemu, I had the opportunity to do preparatory work for the submission. I also helped in the filing of submissions to international and regional courts on behalf of Nega and Alemu.

At this point, their chances for release are still unknown, but the situation remains dire. In a New York Times Op-Ed, “Letter from Ethiopia’s Gulag,” Nega wrote about gruesome prison conditions, including three toilets for about 1,000 prisoners. Alemu’s health continues to deteriorate: After receiving an operation to remove a lump in her breast—without the use of anesthesia—she was immediately sent back to the prison without proper recovery time, and she has since been denied further treatment.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights remains one of the last options for these two journalists. When the Commission convenes its next session on October 22nd, I am hopeful it will recognize their case is admissible and that the Ethiopian government has used the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation to systematically violate the right to freedom of expression. Even if the Commission decides the case is admissible, a decision on the merits is far away. While the ruling on admissability will not immediately free Nega and Alemu, together with more international pressure, the Commission may eventually persuade Ethiopia that the cost of jailing journalists is too high.

Lindsay Church, JD ‘16, will join the Programme in Comparative Media Law and Policy at the University of Oxford this January as a visiting research fellow. While there, she will work on a paper she began this summer, “International Influence on Freedom of Expression in Ethiopia: An Analysis of the Impact of Ethiopia’s Relations with the United States and China.”